The Bioethics Project

At Kent Place School

By Alexandra Sinins ’22

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly expanded the public’s knowledge about the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the United States government agency responsible for public health. Society knows about the CDC related to their announcements about the coronavirus, its dangers, and the best ways for us to protect ourselves. With scientific knowledge ever-changing, the CDC’s ethical role in providing transparent information is quite challenging. This paper explores whether it is ethical for the CDC to act other than with complete disclosure to the public. In other words, is it sometimes ethical for government scientists to withhold information from the public to protect it?

Can the United States government protect us by withholding information about dangerous pathogens? This is one of many complicated issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. The United States citizens expect the government to be transparent and do what is in society’s best interest. But what if providing scary, incomplete, and ever-changing data would cause public panic? The important role of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has been front-and-center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Society looks to our government’s scientific leaders for answers. They are held to the expectation of being truthful. We look for the CDC to meet its public health obligation to protect the nation’s public and be a world leader.

The ethical role of the CDC during COVID-19 is a complicated one. The CDC must balance public health and safety and provide information on a complicated, unknown virus. In the time of social media and constant news, the CDC’s role is even more complicated because it must counter misinformation that is spread. This misinformation has concerned transmission, masking, the dangerousness of the virus, and social distancing.

Using the ethical frameworks of Consequentialism and Utilitarianism, society can analyze the CDC’s decisions on what information to release and withhold. Contrary to the simple view that complete transparency is always the most ethical policy, society can understand that there may be ethical decision-making in selective disclosures by the CDC.

For a nation to function successfully, its citizens must trust their government to act in their best interest. The primary goal of the government is to ensure a nation’s survival and the health of its citizens. This goal is tested to its fullest during a pandemic. That is because ensuring survival may lead to government choices that do not necessarily mean absolute transparency and equal access to information or resources. In short, what does it mean to protect a nation and to ensure its survival? Can citizens trust their government to act in their best interest when these choices are made? If so, there are lessons to be learned from the way the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has approached the COVID-19 pandemic and how information has been supplied to the public.

The government’s responsibility to the public goes hand-in-hand with notions of justice and fairness. We can fairly expect our government to be truthful with us. That is especially true in important, life-or-death matters like a pandemic. The public needs to know, quickly and accurately, the dangers and risks of COVID-19 and how best to protect themselves and their families. This information was often scary and devastating. Information was often incomplete and unclear. Scientists are still learning about the COVID-19 virus for the first time. Nonetheless, we can certainly expect that our government would provide accurate advice, as government scientists were themselves learning about the virus, in order to ensure that the public could protect itself as best it can.

The reasons for these expectations are rooted in ethical concepts. Transparency and justice are linked. The government has an unwritten responsibility to share, as safely as possible, all the information which is then available and reliable. But how can this be done safely and effectively at the outset of a pandemic? This information to be shared is untested and in many ways unknown and based on informed speculation. The scientific “facts” were often changing ones. This paper analyzes the ethical framework of government disclosures in the context of a pandemic. Do the proper roles of government disclosure and transparency vary based on the circumstances, and can a lack of transparency ever be ethically justified?

The COVID-19 pandemic shows why government disclosures during a novel pandemic reflect difficult decisions. When COVID-19 was first identified, its source, makeup, and the implications of the virus were unknown. That is, scientists had incomplete information at the outset of this new pandemic, specifically regarding an entirely new/unknown disease with global implications. Scientists, including government scientists, were doing their best to study the pathogen and to reach conclusions for the public benefit as soon as possible. Society wanted to know how dangerous the virus was and what they could do to protect themselves. At the outset of the pandemic, there was not much talk about potential vaccines because, before they could be developed, scientists had to learn more about the virus and how it could be countered.

The public wanted answers, but there were no real answers to be given. This lack of information was problematic because society could lose faith when the government could not protect the public. Even when certain “answers” were available, like the easy transmission of the virus, and its deadly nature, questions remained about what should be shared with the public to avoid panic. Complete transparency could itself have adverse effects. If specific facts are released without context or pursuant to a response plan, mass hysteria can result.

The CDC was faced with ethical questions surrounding the release of bad news, including the release of information that could cause public panic. Even so, there is a governmental obligation to act ethically and to release accurate and complete information. Even if the public may react badly, the CDC’s responsibility is to provide even intimidating information to the public. If the CDC withholds information, it can be criticized by all members of the public. If the CDC discloses information and panics the public, it may also be criticized. However, the CDC would not be accused of misleading the public by withholding facts. The ethical choice is one that promotes truth.

This paper addresses the ethical implications of the timing and content of United States government disclosures, and, in particular, disclosures by the CDC about the COVID-19 pandemic. It focuses on the impact of information-sharing on different aspects of safety and uses the frameworks of consequentialism and utilitarianism to evaluate the CDC’s actions. Consequentialism is an ethical framework that determines the “rightness” of actions based only on the outcomes or consequences. It will ultimately be compared and contrasted with aspects of Utilitarianism, which is a theory that argues for the most significant amount of good for the greatest number of people.

This paper will address, in the context of the concepts of Consequentialism and Utilitarianism, the timing of critical disclosures about COVID-19, and it will further consider the impact of these disclosures on safety. That timeline of CDC disclosures includes the first date that the virus was identified in the Wuhan Province of China and the subsequent path of the Coronavirus around the world. From the point COVID-19 began infecting those in the United States, the timeline tracks the virus’s path and the government response. With this information, it is important to consider the CDC’s role in the pandemic and what ethical considerations should govern its disclosures.

In the United States, the public expects the government to work for the people and to act ethically. There are core values that are expected. The values of commitment, safety, accountability, and integrity lie within all three government branches and are tested to an extreme during a time as chaotic as a worldwide pandemic. This paper will focus specifically on the Executive Branch and, particularly, the CDC, an Executive Branch agency responsible for public health.

Public health matters are within the province of the Executive Branch. The Centers for Disease Control (“CDC”) is officially a part of the Executive Branch. It is an agency under the general auspices of the Department of Health & Human Services (“HHS”), led by the Secretary of HHS, a member of the President’s Cabinet. The CDC was initially started in 1949 by Dr. Joseph Mountain to help prevent the spread of Malaria, and

“[t]oday, CDC is one of the major operating components of the Department of Health and Human Services and is recognized as the nation’s premier health promotion, prevention, and preparedness agency.”

cdc.gov, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021

The primary job of the CDC is to monitor public health and engage the public. It is clearly outlined and emphasized that the CDC holds a “Bold Promise to the Nation.” It states that the CDC

“[…] commits to saving American lives by securing global health and America’s preparedness, eliminating disease, and ending epidemics.”

cdc.gov, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention divide responsibility for preparedness on different health matters as follows:

Every move the CDC makes, including all statements and information released and kept from the public, reflects on the United States government as a whole and the immense responsibility it holds to every single citizen. Many factors have to be considered, including public perception, for the CDC to release information. Therefore, thinking within the context of consequentialism, it may be argued that, as long as the information is released, it does not matter what the in-between stages are. However, during times of mass panic, possibly brought about by information present, or lack thereof, the goal would then be to ensure that the information is presented to ease this hysteria within society and convey timely, appropriately contextualized, accurate data. With this example at hand, a consequentialist might feel that as long as the result of internal deliberations is disclosure, the duration or content of those internal deliberations is insignificant.

During a Pandemic, what role do scientists have in educating the public? As the Executive Branch agency charged with responsibility for understanding and educating the public about the pandemic, it is important that the CDC communicate trustworthy, scientific and useful, practical information in a timely manner. Does the need to be accurate and to minimize the risk of panic justify entirely withholding or delaying the release of scientific or practical information?

Due to the CDC’s importance as an Executive Branch agency, do their statements carry more weight, and should they be required to hold a more ethical view? In other words, does the importance of the government’s voice in informing the public lead to a greater responsibility to take ethical care in the statements that are made?

Using consequentialism, even if the desired outcome is still provided, there could always be mass hysteria. Delayed disclosure of information could undermine trust in the CDC even if the disclosure were delayed in order to ensure that the information to be shared was accurate. This undermines society’s confidence that the CDC’s actions are in the public’s best interest and therefore proving the information released, at whatever time, to be invalid. Are there other factors that could lead the scientists ethically to withhold information? Whose role is it to determine the public’s good and harm?

All members of a society accept that the government should and does seek to protect and improve health for everyone. The National Cancer Institute best defines the World Health Organization (WHO) as

“[a] part of the United Nations that deals with major health issues around the world. The World Health Organization sets standards for disease control, health care, and medicines; conducts education and research programs; and publishes scientific papers and reports. A major goal is to improve access to health care for people in developing countries and in groups who do not get good health care.”

National Cancer Institute 2021

The actions of the WHO and the CDC should reflect mindfulness of the ethicality of their conduct and should be judged by their outcomes. In short, their actions should reflect this immense responsibility to citizens’ safety and health to provide the resources and opportunities to all citizens. However, each individual has the right to their own autonomy, which might be ignored while looking through a consequentialist lens. Although when they have access to said resources, it is in the individual’s own hands to determine further action and seek or not to seek or to follow or not to follow what the WHO or CDC recommends.

Another pressing issue is whether government agencies in more developed countries are responsible for sharing information, response protocols, and other resources, including vaccines, with less developed countries. Is it ethical to maintain a nationalist lens? The CDC is established to act in the best interest of U.S. citizens. They also have a responsibility to the world by being a developed nation and a worldwide power with the expectation of holding an example and collaborating with other nations for the good of the citizens of the world. As part of the Executive Branch, led by the President, and by representing the United States as a whole, there is an unwritten responsibility to do whatever the CDC can do to preserve public safety. They are responsible beyond non-maleficence and providing essential resources, information, and possible vaccines or treatments to developing nations. This provides the nations with their own autonomy to act in their personal best interest. Therefore, the CDC does have an unwritten responsibility but must maintain a balance of worldwide safety and autonomy on both an individual and national level.

One question that implicates the CDC’s local, national and international responsibilities is how to handle information about the effectiveness of vaccines against new variants or strains of COVID-19. What would be the impact on the public and the CDC if the CDC releases premature or incomplete information about variants and vaccine efficacy? Variants are already in the U.S. and under discussion in the public arena. The CDC has to be concerned about the risk of communicating false or incomplete information. This could cause the public to lose trust in the CDC and possibly other government agencies. It could prompt people to jump to inaccurate or even dangerous conclusions that could cause panic or other injuries. On the other hand, failure to release information from a trusted source could lead people to rely on misinformation or become angry about the lack of transparency. This could also hurt the CDC’s reputation.

The CDC should be primarily concerned first about the health and safety of the United States citizens. To prevent the spread of new strains and to vaccinate as many people as possible is the main goal, so why is this an ethical issue? The CDC could be concerned about their credibility if they release information prematurely. If this was later found to be completely untrue, then the United States public could lose trust in the CDC and possibly other government agencies. The release of partial information or miscommunication to the American citizens regarding vital information could create mass panic. With only partial information, many citizens could jump to dangerous conclusions that could cause other citizens to become panicked and frightened for their own safety.

In contrast, if the CDC did not release any information to the public, many citizens would find misinformation or become angry with the lack of transparency whatsoever. The CDC’s reputation could also be at risk in this situation. Citizens with a lack of knowledge could feel that their safety and autonomy have been ignored and that their voice is deemed unimportant by the government. The CDC must find a correct balance of transparency and provide citizens with all the information to make informed decisions and preserve a sense of personal autonomy. With that being said, it is also important that safety is preserved for the nation and the world as a whole.

The Miriam-Webster Dictionary defines safety as “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss.” The CDC’s role resembles this definition of promoting safety. The CDC’s Bold Promise to the Nation reflects the ultimate goal of promoting safety. However, during the time of a pandemic, the CDC cannot ensure this condition. In fact, the public is at significant risk. Yet, the CDC can try to promote public safety to the best of its ability. But what does that mean in terms of what and when the CDC should reveal vital information? This definition of safety, to some extent, dictates the information that the CDC chooses to reveal to the public. This paper will focus on dividing the meaning of safety into five subgroups: Economic, Social, Physical, Physiological, and Political.

Economic safety can be defined for an individual to predict and maintain a steady income or other resources that maintain a healthy and consistent way of living at the present moment and for that upcoming future. (Homeland Security)

Economic safety for a nation is defined and shaped by the federal government and differs for every country. However, the Department of Homeland Security defines America’s economic security as:

“America’s economic prosperity, and the world’s, dependent increasingly on the flow of goods and services, people and capital, and information and technology across our borders.”

the Department of Homeland Security, 2021

Without this economic security, most of American society would be in pieces due to the economy’s involvement and importance in each person’s everyday life.

In the time of a pandemic, economic security is often in conflict with public safety. That is because keeping businesses open can place the public at risk. However, there is tension here. That is because keeping some businesses is necessary to feed and otherwise to take care of the public. For example, society could not live during the Pandemic if supermarkets were completely shut down. A conflict arises between certain business owners seeking to stay in business and the government’s desire to maintain public safety. The other issue that arises is that closing businesses can also lead to mass panic and public concern. CDC officials must understand that their work and disclosure will have economic effects too. (Probst, Lee, Bazzoli)

Small businesses are most at risk due to pandemic shutdowns. They may not have the funds or investments to hold them over during downtimes. Even large corporations have the risk of shutdowns and downsizing due to the pandemic. Depending on the industry (e.g. restaurants, clubs, and entertainment), these businesses may be at risk of closing altogether. Other businesses have used the pandemic as an opportunity to change their operations to adapt to the pandemic and its needs. This has allowed companies to survive.

International trade has been greatly affected by the pandemic. However, international cooperation is more important than ever. This is especially true about sharing information.

The World Bank describes, “[t]he crisis highlights the need for urgent action to cushion the pandemic’s health and economic consequences, protect vulnerable populations, and set the stage for a lasting recovery. For emerging markets and developing countries, many of which face daunting vulnerabilities, it is critical to strengthen public health systems, address the challenges posed by informality, and implement reforms that will support strong and sustainable growth once the health crisis abates.”

As the pandemic continues and economic repercussions deepen, the world will face irreversible consequences. (The World Bank)

Social safety has a completely different definition during the pandemic. Beforehand social safety meant having a support network and an environment free from threats. During the pandemic, social safety, by definition, includes separation and some type of isolation. While everyone is aware of social distancing requirements, what has not been considered are the social implications and emotional toll on individuals due to the isolation. Should scientists ignore the adverse consequences of isolation to help avoid medical problems from socialization? In other words, when making recommendations, should the CDC consider that recommendations to stay at home or use social distancing may mean that some people will develop isolation-related mental health issues? Are mental health consequences a legitimate concern of the CDC, or should the CDC simply concern itself with advice on containing COVID-19? (Frankovic)

The physical safety of COVID-19 patients is an important topic to be addressed. Scientists know about the need to maintain Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) used to keep patients and medical staff safe. When does physical safety have to be ignored?

Using consequentialism, if an emergency made COVID-19 precautions seem unnecessarily burdensome and counterproductive, what would be the protective measures? By way of example, someone may need to disregard social distancing protocols because of other pressing medical concerns. Patients have been required to go to the hospital for emergent matters other than COVID-19. This has risks to them and others, but it is necessary for their own physical safety.

In life and death matters, would saving a life be worth the two-week and now the one-week quarantine? Using the value of responsibility, it would be ethical to answer yes. Each citizen plays an important role in society, and each citizen, therefore, has a duty to look out for his fellow citizens. If one has the ability to save a life, regardless of the circumstances, one should do everything in their power to do so. However, during the pandemic, there is a large exception to this view. The helpers may have their own responsibilities to keep themselves, their families, or their co-workers safe. So it is often not a simple question of helping others as noble as that sounds. It weighs responsibilities and benefits that must govern our choices as a society during a pandemic. (Gollust) Ultimately, the correct and ethical answer in this situation is the one that protects the individual by putting oneself at risk, by possibly breaking COVID-19 precaution protocols, to help save a life.

The public’s mental health in the United States is most impacted by the information they receive about the pandemic. Should scientists consider the impacts that truthful information will have on the public? Should there be times when vital information is withheld? Is this ethical?

For example, more and more people are being vaccinated. It has not been made clear publicly whether vaccinated people can be carriers of COVID-19 and infect others. It is inconceivable that the CDC does not have an answer to this question. It is plausible that the answer is that vaccinated individuals may not be carriers. If this is the case, and the CDC is withholding this information to prevent people from disregarding distancing and masking protocols or preventing unvaccinated people from doing so under a claim they are vaccinated, this may be considered non-disclosure. But is withholding this information, in those circumstances, and for those reasons, ethical? There is a good argument that it is ethical to promote public safety by withholding information that may lead to reckless behavior. It may be that the information is being withheld so as not to disrupt a society where some individuals feel free to act carelessly, e.g., not complying with social distancing or mask requirements. The CDC perhaps is also trying to prevent more backlash against those who mask. Ensuring everyone does so serves that benefit as well. Let us suppose that the CDC takes the opposite tactic. Would it be ethical for the CDC not to inform the public that vaccinated people are completely safe? The impact of this disclosure would potentially encourage more people to become vaccinated so that they do not need to distance themselves or wear masks. But this would, as noted before, cause a rift in society by dividing people based on their vaccination status. The public’s safety as a whole is not so divided. Perhaps, the CDC is considering that society’s mental health is better served by not releasing this information? (Dartmouth)

Political safety can be defined in many different ways regarding both domestic and international politics. It can be about a nation’s security and dominance relative to other countries in the world. It can also regard an individual or association’s political reputation. (Hanage) Should political considerations govern the disclosures by the CDC? Because the CDC is part of the Executive Branch, it is controlled by the Executive. What happens if the President does not want the information disclosed? This brings about the list of questions:

However, the ethical question can arise: How should the economy of public safety be prioritized over the other? However, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a present need for a balance for economic security, reopening the economy, and prioritizing US citizens’ health and physical safety. A YouGov poll showing the results from May 17-19, 2020, shows the public’s opinion regarding the reopening of most of the economy.

The data shows that most U.S. adults believe it will increase COVID-19 rates and make the wrong decision. However, how does a nation decide to maintain or outweigh this balance? Using the value of responsibility, regardless of the political polarization, the CDC should hold the ultimate power to act in the best interest of its citizens’ physical health, regardless of the economic repercussions. (YouPoll)

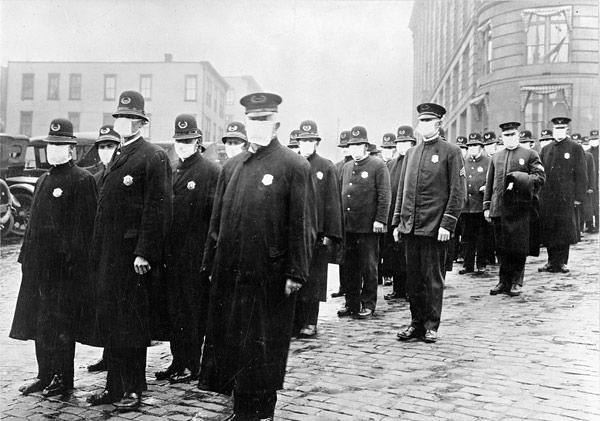

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 is referred to as the largest influenza outbreak of the 20th century. It occurred from the spread of one of the most fatal mutations of the subtype Influenza, H1N1, which originated from birds and was deemed the nickname “Spanish flu.” It occurred in three waves throughout the world. It is estimated that ⅓ of the world’s population became infected with the virus, and deaths worldwide were at least 50 million, with around 675,000 deaths in the United States.

Citizens worldwide and health agencies have much to learn from the prior pandemic regarding government disclosures and responding to misinformation given to the public. The historical context of the earlier pandemic is useful in that we can review the lessons learned. In 1918-1920, there were much more limited means of communication. There was much less advanced scientific knowledge and methods. There was a much less developed international community to share information. All of these circumstances led to a situation where there were severe limitations in educating the public.

In 1918, the United States government had no CDC. There was no federal CDC or equivalent during that period. Communications were really lacking. There was no television, internet, social media, and much slower information to the public. People in the U.S. received information about the pandemic, including where it was, how it spread, who had been affected, primarily from the state government and newspaper sporadic releases of information. As society looks back on that pandemic, society understands that people felt concerned about the inconsistent information release. The experience led in part to the founding of the CDC in 1947 to ensure greater public awareness. (Terry)

Unfortunately, the lack of communication was also accompanied by the release of misinformation to the public. It was first identified in U.S. military personnel and spread throughout the American public. In September 1918, Royal Copeland, Health Commissioner of New York City, announced, “The city is in no danger of an epidemic. No need for our people to worry.” Not even two weeks later, this similar suppression and downplaying of the nation’s health crisis hit the San Francisco Health Officials in the face when they realized the severity of the situation. (Milsten) (Gladstone, Brooke, and Barry) An important lesson learned was that the government misinformation further harmed public safety.

There had to be major corrections to the misinformation coming out. But providing accurate information also led to panic. The government dedicated resources to information; however, by the end of October 1918, Dr. Andrew Milsten described the situation best by stating:

“195,000 people died of influenza in America during October. Funeral homes had to hire armed guards to stop people from stealing coffins. Violence erupted in some areas, with people being shot for not wearing their masks, along with homicides and suicides. An epidemic erodes social cohesiveness because the source of your danger is your fellow human beings. The source of your danger is your wife, children, parents, and so on. So, if an epidemic goes on long enough, and the bodies start to pile up, and nobody can dig graves fast enough to put the people into them, then morality does start to break down.”

Andrew Milsten MD, MS

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Fellowship Director Disaster Medicine and Emergency Management

This intensity was broken down not even a month later, as Dr. Milten went on to describe on November 18, 1918:

“Celebrating the end of World War I, 30,000 San Franciscans take to the streets to celebrate. There is a lot of dancing and singing. Everybody wears a face mask.” But then, three days later, “Sirens sound in San Francisco announcing that it is safe for everyone to remove their face masks.”

Andrew Milsten MD, MS

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Fellowship Director Disaster Medicine and Emergency Management

This description is just a small insight into the severity and the intensity that had taken place in the United States in 1918, but ethically it can be further analyzed.

The ethical framework of the COVID-19 government response is properly compared to the government response from a century ago.

“At its worst, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people worldwide, which at the time was about a third of the Earth’s population. More than 50 million people died of the disease, with 675,000 in the U.S. There is some disagreement on that figure, with recent researchers suggesting it was about 17.4 million deaths, while others go as high as 100 million. Generally speaking, the fatality rate for the Spanish flu is calculated at about 2%.”

Mark Terry, Biospace Contributing Writer (Biopharma)

There was a large disparity of information; however, the US’s primary goal, as standing now during the current COVID-19 pandemic, was to save the most lives possible. The actions which are taken to reach this goal could be deemed as unimportant through the ethical lens of consequentialism. However, using the value of safety and responsibility, each citizen played and continues to play a critical role in the consequences of a pandemic.

Another lesson to be learned was the impact of government advice and the rejection of that advice by many members of the public. Anti-maskers are not new in the United States. Although the Influenza Flu outbreak in 1918 was deemed one of the most fatal spread of Influenza, it still faced a lot of controversy for mask-mandates to be enforced and followed, similar to the present. (Little) California, specifically San Francisco, and many states in the West took mask mandates very seriously and required citizens to wear them for the public’s overall safety. Many enforced the idea that masks during wartime were significant to keep the troops safe and to stop the spread that troops could carry coming back home. However, as the war reached its end, the mask initiative similarly declined, and there were even groups who were so against masks they formed an “Anti-Mask League.”

However, the masks of a century ago were not as effective as the technologically advanced ones citizens wear in the present. The requirements for masks were nonetheless still enforced as much as possible. Many who refused to wear masks, nicknamed “mask slackers,” did so not because they were rejecting science and did not believe in what the nation was going through, but because they valued personal comfort over society’s safety.

Both today and in 1918, many people appear to believe that masks infringe on their personal autonomy, which is more important than the nation’s overall safety. However, this statement is unethical because although it is important to preserve and protect personal autonomy, the nation’s security comes before all else. By stating that one would not wear a mask because of their personal values, they are neglecting their responsibility to society and making a statement that they are more important than the safety and health of everyone in the nation, including healthcare and essential workers who have been working tirelessly to ensure that the safety and health of the country are prioritized. (Little)

“Some experts, such as Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who is something of the public point-man for the U.S. response to COVID-19, project the fatality rate will be about 1%, which is still about 10 times the fatality rate of a typical seasonal influenza of 0.1%.”

Mark Terry, Biospace Contributing Writer (Biopharma)

However, it is dangerous to compare situations that both hold such severity. The advancement in technology has allowed communication to spread as well as new technologies relating to treatments rapidly.

The use of technology has allowed many good and bad consequences to arise from the COVID-19 pandemic; however, overarching research has allowed for new sciences to be explored to save the most people possible. (Terry)

As discussed earlier, the CDC was not present until 1947 at Emory University. This, however, brings up many ethical questions: How would the public’s knowledge have been improved if an organization or government agency, like the CDC, existed in 1918? What is the effect of the CDC’s development as a part of the Executive Branch on citizen’s trust? How do government affiliations change the perception of information? (CDC)

Below is a brief history of the CDC’s early information releases regarding COVID-19 and the ethical issues pertaining to this communication.

The COVID-19 first grew in intensity in Asia and Europe. On January 9, 2020, the WHO expressed concern about 59 cases of COVID-19 in the Wuhan Province in China. (American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation). On January 20, the CDC disclosed that three U.S. airports would begin screening for COVID-19. Those airports were at major locations, JFK in New York, San Francisco International, and Los Angeles International Airports. However, most of the Wuhan flights were arriving in the United States, and the American public is still allowed to travel freely, with no mask mandate at this point. Yet, one day later, the CDC confirmed the first Coronavirus case present in the United States, and a Chinese Scientist verified that COVID-19 is spread through human transmission.

During this time, China was under quarantine. Yet, the United States did not declare a Public Health Emergency until three days after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Global Health Emergency because, at this point, there have been more than 9,800 confirmed cases and 200 deaths worldwide. The United States did not declare COVID-19 a national emergency until two days after WHO claimed COVID-19 a pandemic. By doing so, the WHO enlisted the aid of the federal government funding to combat this health crisis. California was the first state to launch a stay-at-home order on March 19, and many states followed this example.

Below is a visual representation of the information of the timeline of disclosures:

This beginning point for the release of information was a chaotic time for all world citizens and a time for world leaders to create a plan. Since then, the CDC has been the primary source of information for the American public to follow. The information supplied by the CDC since that time has been relied upon for accuracy and completeness. Yet, the CDC has also contributed to public panic by some of its disclosures.

In September 2020, a report from the CDC caused much hysteria on social media as many thought the CDC was relaying that COVID-19 was not as deadly as previously indicated. (Aarons) Jared Aarons, an ABC News reporter, outlines in his article from 10 News that

“The report breaks down what doctors list on patients’ death certificates and found that “for 6% of the deaths, COVID-19 was the only cause mentioned.” It also says that an average of 2.6 additional conditions were listed on death certificates, including COVID-19.”

Jared Aarons, Morning Show Reporter for ABC @10News in San Diego

However, this was quickly clarified by other experts and doctors.

It further explained the extent of damage the Coronavirus has done to many bodies, causing other organ systems to fail and initiate or highlight previous medical conditions a patient may have. He went on to state,

“According to the CDC, 42% of COVID-19 death certificates also listed Influenza or pneumonia. Respiratory failure was listed on 33% of the death certificates. Hypertensive diabetes was listed on 22%, while diabetes was on 16%. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome was on 14% of the death certificates. Cardiac arrest was 13%.”

Jared Aarons, Morning Show Reporter for ABC @10News in San Diego

This disclosure was the initial cause of public panic. Many thought that the CDC has not been correctly conveying information and essentially had been lying to the public to end the pandemic faster. This manifested itself in two ways. There was concern that there was an exaggeration of COVID-19 mortality rates where many death certificates listed COVID-19 as the cause of death, where it might not have been. There was a second concern that there may have been an exaggeration of the risks from COVID-19. This is even more complicated because COVID-19 has undetermined consequences for people’s underlying conditions, which may worsen their condition. There was confusion about the accuracy of information relating to the harms and mortality involved with COVID-19 and a suggestion that the public may have been provided with misinformation. Others believed that this miscommunication could be used to further emphasize their lack of trust within government agencies, such as the CDC, and as further backing to their rejection of science.

Through consequentialism, if the result would be the end of the pandemic, how the CDC convinced the public to follow the guidelines would be disregarded. However, the CDC and all government agencies are responsible for doing what is in the United States citizens’ best interest, so again, it does not matter how they get there as long as they get there.

Vaccination is another example to further analyze the ethicality of the CDC’s release of information. There has been a lot of controversy regarding those who have already been infected with COVID-19 getting vaccinated. Throughout different clinical trials, it has been proven that there is no additional benefit for that population. Yet the CDC has stated that those who have previously been infected with COVID should still receive the vaccine. However, they are not as high on the priority list because they could have antibodies or other protection forms.

Senator Rand Paul challenged the CDC’s statement and encouraged them to correct it for two reasons. First, the trials didn’t show a benefit for that population; second, people who didn’t have antibodies should be prioritized for vaccination over people who did. The CDC still has posted on their government official website:

“Yes, you should be vaccinated regardless of whether you already had COVID-19. That’s because experts do not yet know how long you are protected from getting sick again after recovering from COVID-19. Even if you have already recovered from COVID-19, it is possible—although rare—that you could be infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 again.”

cdc.gov, Frequently Asked Questions about COVID-19 Vaccination: “If I already had COVID and recovered, do I still need to get vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine?”

In private conversations with Senator Rand Paul, the expressed concern was about having a message out there that would be construed as discouraging vaccination. (Lee)

An example of this was outlined in an article written by Michael Lee published in the Washington Examiner, focusing on Senator Rand Paul’s accusation of the CDC lying to the public about the vaccine’s effectiveness of those who have already been infected COVID-19.

Paul tweeted out and shared an article from Full Measure, which essentially supported the public’s vaccination as a whole, even those who already had the virus.

“People who have had the disease, given that there are limited doses right now, we’re suggesting that those people wait,”

Captain Amanda Cohn, MD

Chief Medical Officer for the Vaccine Task Force and the National Center for Immunization andRespiratory Diseases

Dr. Cohn was backing up claims of Representative Thomas Massie. However, CDC officials claimed that the vaccine would still be effective for those who have previously been infected, but they should not be prioritized since there is a limited supply. Through an ethical lens, CDC officials had a responsibility to clear up this misunderstanding; however, the CDC did not issue any clarifying statement.

In terms of the pandemic, the stakeholders comprise the entire nation and the rest of the world. How the United States responds to the pandemic will impact the country and could serve as an example for the world.

In regards to the public, everyone is at risk and needs truthful information. Those who scientists deem to be at the highest risk must closely abide by safety recommendations. There is a significant movement of denial advocates who claim that COVID-19 is a “hoax” and no more dangerous than the flu. Unfortunately, those deniers can have a major impact on themselves and society. However, regardless of an individual’s personal views of COVID-19, it is undeniable that it is an airborne virus and that it has killed millions worldwide. Frontline workers are put at the most risk and workers in the healthcare fields and other fields essential to keeping the nation running need special protection. They are designated as the first group to obtain vaccines.

Scientists have also deemed who else should be given priority. Some groups, including children without underlying health conditions, have not been deemed a priority to receive the vaccine. A significant question is whether scientists truly believe that there are groups that are less at risk. If not, then the ethics of withholding that information arises. Is the reason why this information is not provided to prevent panic with families rushing to vaccinate their children? Is this a good idea and justified?

Through ethical analysis, one can also look through Utilitarianism, the most good for the most people, by looking out for the good of the nation’s public. The primary goal of the CDC, as outlined before, was to maintain the best interest of the public (1) how does that compromise or disregard the individual needs of specific citizens? (2) Would it be ethical to do things in the best interest of those most affected by the Pandemic?

Using a utilitarian analysis, the CDC has ethical justification for its actions because every move or decision made, especially in a time as stressful as a pandemic, is to maintain safety for society as a whole.

Issues of specific needs or prioritizing individuals, such as an essential worker, could be seen as breaking utilitarianism because it does not focus on the “most people.” However, it plays on the idea of social utility. It could potentially fit within utilitarianism because by prioritizing the lives of those who bring the most good and safety into society as a whole, it would be doing the most good. By contrast, consequentialism cannot give us guidance on how to prioritize.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, the ethical question arises of whether benefits to the public can justify unethical behaviors by scientists. In particular, may scientists provide incomplete or misleading information to protect the public and ensure that society continues to run smoothly? Who makes these judgments?

To look through the ethical framework of consequentialism, the question most commonly asked is: Do the ends justify the means? Although each case-by-case example is dependent on the ends, and again the person examining it, however, one can see two examples of questions that are important regarding the CDC. First, if quarantining has only a marginal positive impact, would a scientist be justified in exaggerating its benefits to cause the public to quarantine? For another example, if scientists know that there is a huge risk of serious illness, is it ethical to downplay a risk for a time, to ensure that there is no public panic, which could cause an even greater demand for a vaccine?

Consequentialism can also be considered when analyzing this question: What does it mean? Could scientists use unethical means to promote false or misleading information? Can the CDC use official government resources to promote misinformation? Under what circumstances?

Or, contrastingly, the question: At what cost? What is the long-term cost of unethical or misleading information provided by scientists?

Withholding certain information could lead to avoiding the problems or mass hysteria, but it comes at the risk of the public losing faith in government. By doing so, the government is at risk for the judgment of disregarding the unwritten rule of government responsibility or the risk of long-term adverse view of government. Without providing enough information for each individual to make an informed decision infringes on informed consent and could be seen as infringing on autonomy. The slippery slope of society that does not trust the government has been previously shown as systemic throughout our society, disproportionately affecting individuals of color as well, and with lack of transparency comes to lack of trust.

Scientists should be free to relate truthful information to the public. However, extenuating circumstances, such as during a pandemic, allow scientists to consider more extensive societal needs when disclosing information. These needs may include withholding dangerous information, which could have negative consequences if it is revealed. It is not enough to say simply that all scientists should always disclose full and truthful information, regardless of the consequences. It does society no good to be informed that information will lead to chaos and society’s disruption. Once this type of misinformation is allowed, there must be rules to prevent it from occurring except in unique circumstances. Therefore scientists must be free to use their own ethical judgment regarding the responsibility to the public. Otherwise, scientists are expected to live in an unrealistic world where their words can be disruptive without consideration. All in all, scientists and health agencies, such as the CDC and WHO, can justify a lack of transparency through a consequentialist lens, overriding personal autonomy.